Indigenous, traditional and local knowledge: Engaging equitably with diverse ways of knowing

By Kaliana Conesa, Vesper Meadow Graduate Student Collaborator

Author’s Note: I begin by acknowledging the limits and subjectivity of my perspective: I gather these reflections as a non-Indigenous person of Latina and mixed European descent, dedicated to participating in the ongoing work of decolonizing my research and practice as a scholar, activist and human. Humbly I seek guidance at all turns; I attend closely to diverse voices, teachers and friends who continually expand my patterns of knowing and doing. I am deeply grateful to—and delighted by—those who challenge me to expand my perspectives.

Indigenous ways of knowing

Across the incredible diversity of global cultural groups, fundamental human practices unite social experience. All thriving cultures develop complex, adaptive and dynamic systems for understanding and responding to the world around them. Western-European sciences name this epistemology—or, more prosaically, “systems of knowledge.” For most people and cultures, the ways in which they organize information about the world around them is tightly bound with their worldview—how they understand their place and meaning in the scheme of things. Indigenous peoples and local communities have evolved highly nuanced, systematic and powerful knowledge systems to observe; order; explain; predict; adapt, interact and respond to the particular habitats of their ancestral homelands—as well as to lands in which they have settled more recently. These ways of knowing are profoundly place-based, transmitted across generations, and act as deep reservoirs of knowledge about the local ecology. This rich, detailed knowledge is often described as traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), or Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK). A vital feature of traditional knowledge systems is that human and social elements are understood to be part of a holistic ecological tapestry including living and non-living beings. Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars, knowledge practitioners, activists and community leaders have spoken to what TEK means to them and their community (1). As but one example, I refer to the words offered by the Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo Network of Native Hawaiian scholars, activists and Tribal members (2):

“Pre-overthrown Native Hawaiians developed customs and traditions around food and environmental stewardship based on intimate knowledge and expertise derived from long-term, multi-generational observations of the natural world.”

Children planting taro at the 2019 E Alu Pū Gathering. Photo by Kauila Niheu

Other voices emphasize that traditional knowledge does not imply static knowledge. Both historically and ongoingly, traditional knowledge holders are highly attentive to subtle ecological shifts, and respond by adapting. Traditional knowledge is innovative knowledge, with new techniques, technologies and interpretations developed according to changing circumstances. At the same time, many cultural knowledge holders recognize in TEK a core body of knowledge which has remained remarkably stable across time. The violence of colonial history has severely disrupted traditional knowledge, yet TEK has demonstrated incredible resilience. Its ongoing practice is fundamental to cultural continuity. Robert McDonald, Communications Director for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, speaks vividly of the joined resilience and innovation marking the traditional knowledge of his people. He celebrates their cultural survival as he reflects on Congress’s recent —and long overdue—return of the National Bison Range to Tribal management:

“It’s pretty incredible the survival story you’re looking at, that somehow, through all of this, and we hear the stories of our parents, our grandparents, our great-grandparents, of, frankly, being right at the brink of not making it. But yet, somehow, we’re here, and we’re growing. And we’re getting stronger. We’re getting smarter. Well, I don’t know if we’re getting smarter, but we’re learning new tools.”

Bison roaming in the 18,000 acre National Bison Range, now under management of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. (Pic. USFWS)

His humorous interjection—“I don’t know if we’re getting smarter, but we’re learning new tools”—underscores the ever-evolving character of the traditional knowledge which has nourished Indigenous peoples and their habitats throughout colonial upheavals. The work to rediscover, repair, recreate and reintegrate traditional knowledge is essential to the ongoing reparation of rights and sovereignties. Engaging in this difficult work is a responsibility—and opportunity—shared by everyone.

Science is inseparable from culture

Many Indigenous scientists describe their relationship with Western and Indigenous ways of knowing non-dualistically. A recurring theme articulated by Indigenous scientists is that these systems of knowledge are distinct, and in many ways are complimentary. In an interview on podcast Science Friday, Dr. Annette Lee, astrophysicist and artist at St. Cloud State University—identifying as mixed-race Lakota—stresses that science is always embedded in the culture of a particular place and time. As an Indigenous astronomer, she is steeped in both Western European and Lakota ways of knowing. She reminds us that these systems are the products of particular cultures, and that Western science “...has grown out of one culture, and...there are many other cultures that are a part of this planet...those cultures have also done science. And so we need to widen what we mean by science.” (4)

To recognize that our ways of describing and understanding the world are particular to our own cultures involves imaginative leaps into the unknown. For people of European descent, there is an important first step: Acknowledging that Euro-centric ways of knowing are but one way of understanding the world, the product of a particular culture and history. Western science emerged as a dominating paradigm not because it is more accurate, descriptive or powerful, but through violent processes of removal and repression. Indigenous ways of knowing continue to be marginalized and trivialized by mainstream science. Critically examining how Western European science continues to dominate the teaching, dissemination and practice of knowledge is crucial to the work both of repairing relations between Indigenous and settler societies, and cultivating more inclusive ways of knowing.

Researchers, teachers, students, policy makers—and the general public as a whole—have the opportunity to share in the responsibility of cultivating equitable cross-cultural relationships. Like all relationship-building, this begins with an authentic connection between human beings, founded on a willingness to listen and engage with openness. What this engagement looks and feels like always depends upon the people involved—upon their expectations, biases, goals and hopes. But by committing to listen and attend comes the chance to reflect upon and reframe our habitual patterns of thought. This is often a difficult and uncomfortable process; like fish unaware of water, we do not always have access to those ways of knowing in which we are immersed. The following discussion presents the very practical ways in which diverse people are coming together to cultivate expansive, reciprocal and respectful approaches to knowledge in addressing urgent social-ecological needs.

Knowledge sovereignty, cultural appropriation, and respecting traditional knowledge

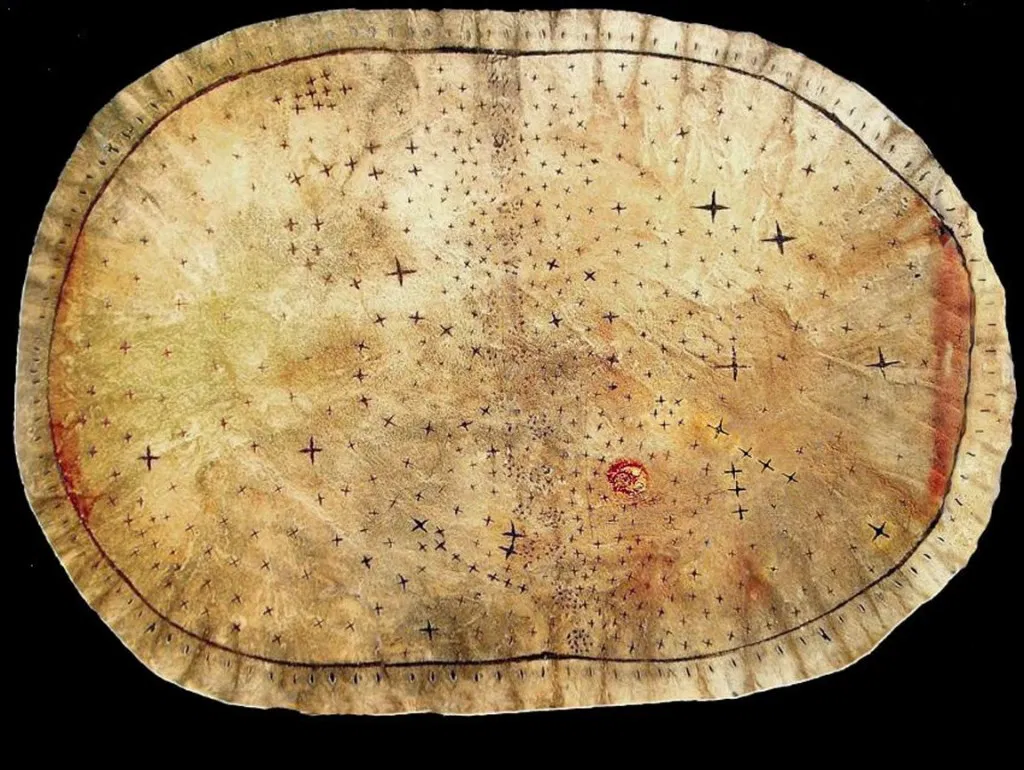

Skidi-Pawnee buckskin starchart, approximately 300 years old. (Pic. Vassar College)

Practitioners of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) hold reservoirs of intimate knowledge about their environments unparalleled in their nuance, complexity and scope. For this reason, scientists, land managers and policy-makers increasingly seek traditional expertise in the urgent efforts to address climate change, habitat loss, health disparities, and other global crises. The intentions behind these efforts may be good, but, too often, non-Indigenous stakeholders fail to respect the knowledge sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. Respecting knowledge sovereignty means—at the very least—recognizing that individuals and communities are sovereign custodians of their personal, community and cultural knowledge. Because TEK is not a static body of information that can be transcribed, copywritten or patented in its entirety, but a complex network of knowing distributed across persons, spaces and times, there are great gaps in what non-Indigenous actors recognize and engage with as knowledge. This gulf is rooted both in ongoing power asymmetries and fundamental differences between Western and Indigenous ways of knowing.

The failure to recognize traditional knowledge practitioners and cultural groups as the proprietors of their knowledge has a long and painful history. Much of this history involves willful appropriation of cultural knowledge, an injustice which continues to be enacted. However, in projects involving Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants, cultural appropriation is also committed unknowingly. This is partly because Western-European society is dominated by a techno-scientific knowledge system which has difficulty accommodating other ways of knowing. Many non-Indigenous people trained in Euro-centric science fail to recognize the complexity of other cultural knowledge systems. Ron Reed, a Karuk biologist, dipnet fisherman and spiritual leader, explains how cultural appropriation can occur as a result of divergent worldviews in the context of burning practices (5):

“Well-meaning attempts to use particular ideas or practices by non-Native agencies have cued into the ecological benefits of traditional management, but have followed Western assumptions about the both the nature of knowledge and the separation of nature and culture. In so doing they fail to see the fundamental interconnections between the ecological and the social. When non-Tribal agencies and organizations use their (often) greater institutional capacity to attempt to adopt and use elements of Karuk TEK (e.g. burning) these actions becomes a form of cultural appropriation and deprive the Karuk community of the opportunity to carry out their own culture”

As Western scientists and policy-makers increasingly recognize the power of traditional land management practices, there is the risk that these practices will be removed from their cultural contexts. Members of the Karuk Climate Change Projects stress the interdependence between cultural burning practices, traditional foods, and Karuk identity. “Management is culture,” and land management is a deep expression of traditional knowledge. The practice of traditional knowledge profoundly shapes the landscape and its biodiversity even while the landscape shapes cultural identity—forming a dynamic network of reciprocity essential to cultural and ecological resilience.

Indigenous-led co-design projects and re-framing biases: Practical models for cross-cultural engagement

The Karuk Climate Change Project exemplifies an Indigenous co-design process, in which Indigenous peoples lead social-ecological initiatives with diverse cultural partners. Co-design projects are centered around the invaluable and irreplaceable expertise of TEK. The collaborative process is guided by a respect for traditional knowledge as diverse partners articulate shared visions, practices and projects. For such projects to support the goals and values of their members, non-Indigenous partners have a responsibility to undertake the work of decolonizing the ways in which they conduct research (6). This begins with the often-uncomfortable process of critically examining habits of behavior and thought which continue to replicate inequalities. Scholars studying the power of implicit bias stress that biases are fundamental to human psychology: moving beyond them requires not harsh judgment or chastisement, but a patient and sustained scrutiny of our beliefs (7). While aspects of this work will always be personal and internal, the process of re-framing biases is richer in diverse company. By intentionally engaging with folks from cultural groups other than our own, we have the opportunity to regard deeply held assumptions in a clearer light.

The imperative to challenge dominant paradigms may feel abstract or even daunting. Recognizing the significant challenges to cross-cultural bridge-building, a growing network of people are reflecting and sharing the many ways this process plays out on the ground. In a New Zealand workshop involving more than 30 Indigenous and non-Indigenous scientists from diverse cultures, participants brainstormed best practices essential to co-design projects (*8). These practices center around the need to position Indigenous ways of knowing at the forefront of research. Actually, doing this means shifting away from Euro-centric models for crafting research, policies, non-profit building and other initiatives. The co-creation of new models for relating involves recognizing diverse worldviews as equally valid and complimentary. This is not an abstract process. It is located in space and time, and how spaces and timescales are framed matters greatly. Participants in the New Zealand workshop voiced the importance of planning project timelines to spaciously accommodate the slow work of relationship-building; convening discussions in forums chosen by Indigenous participants; clearly articulating how, where and why information will be gathered; and carefully considering how to share the benefits of knowledge old and new.

In another large-scale workshop, the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) articulated approaches to engaging equitably with Indigenous and traditional knowledge. Through a process of deep dialogue, a fundamental theme emerged: when diverse cultural partners come together with the goal of sharing and co-creating knowledge, approaches on the ground will be heterogeneous and varied. It is the “...attitudes framing the exchange” (emphasis added) that unify these collaborations. Equitable exchanges are guided by core principles: Respect for diverse knowledge systems, trust, reciprocity and equal sharing.

When these priorities are built into the very bones of collaborative work, spaces are opened in which deeply-held assumptions—about power and authority, life and earth origins, conceptions of time and space, and perceptions of future pathways—may be meaningfully challenged.

Participants working across wide-ranging projects committed to the equitable exchange of diverse ways of knowing continue to reflect upon and share their experiences, enriching the resources that nascent endeavors may draw upon.

Forging solutions to meet the urgency of current social-ecological crises requires nothing less than this courageous, expansive and humbling collaboration.

Sources

1. Hoover E, Mihesuah DA, eds. Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States: Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments and Regaining Health. 2019. University of Oklahoma Press.

2. Chang KKJ et al. 2019. Kuaʻāina Ulu ʻAuamo: Grassroots growing through shared responsibility. In Hoover E, Mihesuah DA, eds. Indigenous Food Sovereignty in the United States: Restoring Cultural Knowledge, Protecting Environments and Regaining Health. 2019. University of Oklahoma Press.

3. Flatow I. (Producer). (2021, February 5). National Bison Range Returned to Indigenous Management. [Audio Podcast]. Retrieved from https://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/bison-range-flathead-reservation/#segment-transcript.

4. Flatow I. (Producer). (2019, September 6). Widening the Lens on a More Inclusive Science. [Audio Podcast]. Retrieved fromhttps://www.sciencefriday.com/segments/indigenous-science/

5. Karuk Climate Change Projects. 2016. Chapter 1: “Management is Culture:” Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Practice of Traditional Management. Retrieved from https://karuktribeclimatechangeprojects.com/chapter-1-management-is-culture-traditional-ecological-knowledge-and%E2%80%A8the-practice-of-traditional-management/

6. Smith, LT. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books. A large body of Indigenous scholars and activists offer detailed discussions on the work of decolonization. As an excellent starting point, refer to this foundational text by Maori scholar-activist Linda Tuhiwai Smith.

7. Tippet K. (Producer). (2018, August 23). The Mind is a Difference-Seeking Machine. [Audio Podcast.] Retrieved from https://onbeing.org/programs/mahzarin-banaji-the-mind-is-a-difference-seeking-machine-aug2018/For an excellent interview with a leading scholar of implicit bias, Dr. Mahzarin Banaji, refer to the podcast.

8. Parsons M, Fisher KT, Nalau J. 2016. Alternative approaches to co-design: insights from indigenous/academic research collaboration. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability (20):99-105. DOI: 0.1016/j.cosust.2016.07.001

9. TengöM, et al. 2012. Dialogue workshop on knowledge for the 21st century: indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge, science and connecting diverse knowledge systems. Workshop Report. Retrieved from https://swed.bio/wpcontent/uploads/2017/05/Guna_Yala_Dialogue_Workshop_Report.pdf